Tonight, I shall be at a dinner at New York’s India House, remembering the co-founding member of the club who died 100 years ago today – Willard Dickerman Straight.

Tonight, I shall be at a dinner at New York’s India House, remembering the co-founding member of the club who died 100 years ago today – Willard Dickerman Straight.

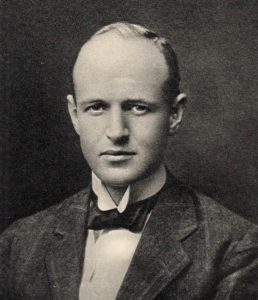

He was born in Oswego, on the New York shore of Lake Ontario, in January 1880. His parents, school principal Henry and teacher Emma, had both died of tuberculosis by the time Willard was 10, and he and his sister were raised by friends of Emma. He found the arrangement frustrating and was expelled from school, but a year at a military academy helped him adopt a more disciplined approach to life, and he went on to study Architecture at Cornell, graduating in 1901.

From the outset, his career took an international focus. He joined China’s Imperial Maritime Customs operations, helping to maintain an orderly customs function, and regulate commercial traffic on the Yangtze River. He served with the US diplomatic service in Seoul, Havana and the Chinese city now known as Shenyang. Then, fluent in Mandarin, he moved into business and became the representative of a group of US banks negotiating a large international loan to China.

It was in Beijing that he played host to a wealthy young New Yorker on the Chinese leg of her world tour, Dorothy Straight. There followed a blissful two weeks of walks, rides, dinners, late-night conversations and serenading, and then more than a year of intense, long-distance correspondence. The pair were deeply in love, but there were questions over Willard’s eligibility.

His prospects brightened considerably when he returned to New York in the summer of 1911, having played a significant role in the successful conclusion of the loan negotiations with China. Now he had status and prospects to sit alongside the love and trust which had shone through in his many letters. They married in Geneva.

Wedded life in Beijing proved far from blissful – 2,000 years of Chinese imperial rule were drawing to a violent end, and it took 20 US marines to rush Willard and his bride to safety, Dorothy in a rickshaw with her maid in her lap.

They returned to the US, and Willard’s friend Bill Delano designed a fabulous Fifth Avenue mansion to complement their country home in Long Island’s Roslyn. Three children arrived in quick succession; Whitney, Beatrice and Michael. Willard and Dorothy founded a progressive magazine, The New Republic, and high political office would surely have followed had Theodore Roosevelt been successful in his attempt to return to the White House he had left four years earlier.

But the 1912 election fell to Woodrow Wilson. No fan of dollar diplomacy, he renounced the loan to China, and Willard’s career lost traction just as Wilson procrastinated over whether to take the US into the Great War. Unable to find a role in the State Department, Willard joined the Adjutant General’s Reserve Corps as a Major, and arrived in Paris on Boxing Day 1917.

His war was neither heroic nor bloody – much to his personal frustration, his skills were too precious to risk in the battlefield. He simply helped make America’s war more effective. His first task was to implement the War Risk Insurance Bureau’s new life insurance policy for US servicemen. Within seven weeks, with a complement of fewer than 100 men and utilising vehicles borrowed from the Red Cross and huts from the YMCA, he wrote $1.25bn of policies on the lives of a quarter of a million personnel scattered across France –a remarkable feat.

His paper on logistics – the movement of troops and engineers, artillery, aircraft and tanks, the supply of food, water and ammunition, the maintenance of roads and the evacuation of the wounded – was adopted as the standard American Expeditionary Force manual, and, unusually for a reserve officer, he was sent to lecture on the subject at the US Staff College in Langres.

For the last month of the war, Willard was based at the headquarters of Marshal Foch, Supreme Allied Commander. Here, he reported to Colonel Mott, the liaison officer between Foch and the Commander of the American Expeditionary Force, General Pershing. On 10 November, with the rest of the team back in Paris, he was the last American there. Before dawn the next morning, he took the call confirming the wording of the Armistice, and that it would come into effect at 11am.

Willard was immediately drafted in to the US delegation preparing for the Versailles peace talks. Now he was the right man in the right place. An American with a truly global outlook and with years of international negotiating behind him, he was clear about the role America had to play. He was fearful that Britain and France would demand too high a price of Germany, and believed that it was up to the US to negotiate a lasting peace in Europe.

Cruelly, a week after the Armistice, Willard was struck down with Spanish Flu, the contagion that would kill more people than had died in the war, and would wipe a dozen years off average life expectancy in the US. Pneumonia set in, and in the early hours of Sunday, 1 December, he died. He was just 38. As Bishop Brent, senior chaplain to the US Forces, said at his grave, ‘His organising genius was exactly what the moment needed. We had thought of him as one of those destined and prepared to make a valuable contribution to the reconstruction of life in the new era that is at its dawn. But it had been ordered otherwise.’

Seven years after his death, Willard Straight Hall opened its doors at Cornell, as one of America’s first purpose-built students’ union buildings. Funded by Dorothy and designed by Willard’s old friend Bill Delano, the imposing building makes highly effective use of the campus’ Libe Slope – walk the 40 paces or so from the front door to the Memorial Room, and there are now five floors beneath you. The inscription over the imposing stone fireplace in the Memorial Room is drawn from the ‘if anything should happen to me’ letter Willard left for young Whitney. It concludes, ‘Hold your head high and your mind open, you can always learn.’

It is highly appropriate, therefore, that one of tonight’s talks will be given by Cornell’s Dean of Students, Vijay Pendakur. He has called it, Remembering Willard Straight: A Vision for Dialogue Across Difference at Cornell.

‘Dialogue across difference’ sums Willard up very well. 100 years on, he is still what the moment needs.