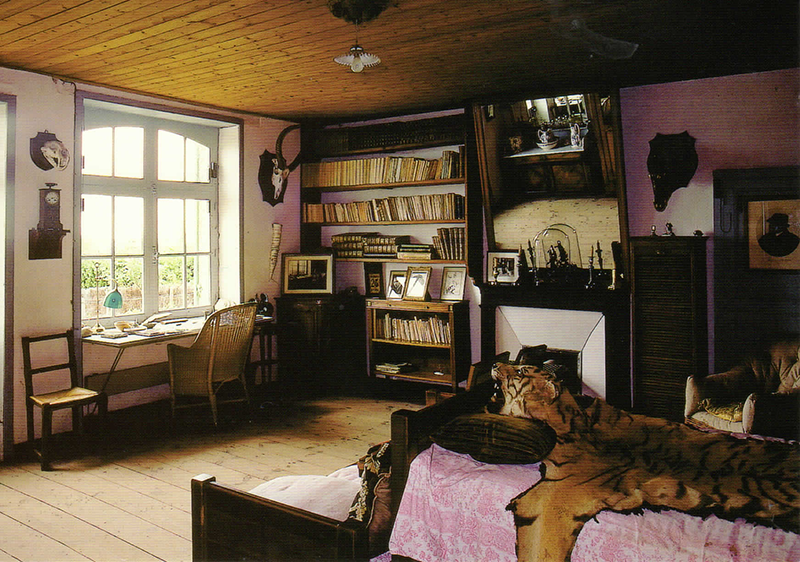

This isn’t where I write – though I wish it were. It’s the place Georges Clemenceau retired to after losing the French presidential elections of 1919. It’s in St-Vincent-sur-Jard, about 30km down the Atlantic coast from Les Sables d’Olonne.

When I visited the small, single-story cottage, separated from the sea by an informal garden, I was most impressed with the way Clemenceau went about his writing and reading. He kept within easy reach of his desk the 100 or so books which he needed for his current assignment. Out in the hall were bookcases lined with a further 1,000 volumes, which he culled regularly.

When I visited the small, single-story cottage, separated from the sea by an informal garden, I was most impressed with the way Clemenceau went about his writing and reading. He kept within easy reach of his desk the 100 or so books which he needed for his current assignment. Out in the hall were bookcases lined with a further 1,000 volumes, which he culled regularly.

Apart from the book-culling (which I consider pretty close to infanticide) I adopted the set up in my own study.

Without even needing to stand, I can grab from that top shelf to my right any of the most well-informed texts on Whitney Straight’s family. To the right of the dictionary and thesaurus sit Herbert Croly’s Willard Straight; WA Swanberg’s Whitney Father, Whitney Heiress; Michael Young’s The Elmhirsts of Dartington; and After Long Silence, by Whitney’s brother Michael. Jane Brown’s recent biography of his mother, Angel Dorothy, clearly hasn’t resurfaced from some holiday reading.

Without even needing to stand, I can grab from that top shelf to my right any of the most well-informed texts on Whitney Straight’s family. To the right of the dictionary and thesaurus sit Herbert Croly’s Willard Straight; WA Swanberg’s Whitney Father, Whitney Heiress; Michael Young’s The Elmhirsts of Dartington; and After Long Silence, by Whitney’s brother Michael. Jane Brown’s recent biography of his mother, Angel Dorothy, clearly hasn’t resurfaced from some holiday reading.

Shelf two holds the most essential motor racing and civil aviation books, and the RAF and PoW escape material lies on the next shelf down. On the desk beyond the laptop are stacked Peter Pugh’s three volumes on Rolls-Royce, The Magic of a Name, and memoirs referring to Whitney’s years with BEA and BOAC, which helped with my transcription of the dreadful handwriting in his diaries.

So, welcome to my cockpit. When old Georges looked up in search of inspiration, he stared out on a wildflower garden and an ocean, whereas I just have a suburban road for company. But I reckon he’s helped considerably with my productivity.